Inherited

Retinal Diseases

Artist Paul Castle isn’t letting an inherited retinal disease stand in the way of his dreams—and now a clinical trial is giving him hope for a cure

Paid Advertiser

Paid Advertiser

CONTENTS

Health Monitor Living IRD

The basics

Understanding retinal diseases

Get the low down on the different types of inherited retinal diseases (IRDs) and how they are diagnosed.

You and your care team

Why genetic testing is key

Finding the cause of your IRD could open doors to breakthrough treatments.

Q&A

Answers to your top questions about IRDs.

True inspiration

Photo by Morgan Belieu

Cover photo by Morgan Belieu

“Vision loss can’t slow us down!”

Paul Castle, Adriann Keve and Sean Brennan share their top tips for managing life with vision loss.

Understanding inherited retinal diseases

Paid Advertiser

Paid Advertiser

What is an IRD?

Inherited retinal diseases (IRDs) are a rare type of genetic eye disorder that cause vision loss and complete blindness in some cases. They occur when a person inherits a mutated gene needed for vision, which can then affect the gene’s ability to function properly. Vision loss varies in severity, depending on the type of blinding retinal disease.

The common types of IRDs

• Choroideremia: A type of IRD that starts in childhood and worsens over time (progressive). Early symptoms include night blindness then tunnel vision and central vision loss. This type mostly affects males and causes deterioration of the retina cells and choroid, the nearby network of blood vessels and connective tissue.

• Cone-rod dystrophy (CRD): A group of progressive IRDs that cause light sensitivity, loss to central vision and color vision followed by loss of side vision. It first affects the cones in the retina needed for color vision and fine detail, followed by the rods in the retina necessary for night vision. Symptoms usually start in childhood.

• Leber congenital amaurosis (LCA): A type of blinding retinal disease that causes severe vision loss in infancy or early childhood. It affects both the rod and cone cells and is associated with other eye problems like light sensitivity and farsightedness.

• Stargardt disease: A type of IRD that causes central vision loss in childhood or adolescence and may cause difficulties with color and night vision over time. Stargardt disease damages the macula, the part of the retina needed for central and sharp vision.

• Retinitis pigmentosa (RP): A group of eye diseases that cause night blindness followed by progressive loss of side and central vision. It first affects the rods then cones in the retina. RP may occur in childhood or adulthood.

How they are diagnosed

If you are experiencing vision problems, make an appointment with an ophthalmologist, who will take a detailed account of your symptoms and medical history as well as your family history. If they suspect you have an IRD, they will conduct a clinical exam, which may include one or more of the following tests:

Dilated eye exam.

In this exam, your doctor uses special eye drops to dilate your pupil to better view the back of the eye. They can then use magnifying glasses to check for overall eye health and identify any issues.

Visual field test.

In this exam, your doctor uses flashes of light to check for problems with your central and peripheral vision.

Color photography.

In this test, a photograph is taken of the back of the eye to identify any signs of disease.

Autofluorescence tests.

These tests can measure patterns of pigment abnormality of the retina.

Electroretinography.

This test measures the electrical response of the rods and cones (light-sensitive cells) in the retina to identify any problems.

Optical coherence tomography.

This noninvasive scan produces an image of your retina and can identify any thinning, swelling or thickening.

Genetic testing.

In this test, a blood or saliva sample will be sent to a lab to confirm or dispute if you have an IRD and identify which gene or genes are affected. It may also be used to determine clinical trial eligibility. In addition, there’s currently an approved gene therapy for a specific mutation, and while it won’t work for everyone, it has dramatically improved eyesight for certain people who have tested positive for that mutation.

Diagnostic testing for IRD can involve more than one appointment with your eye doctor. But it’s important to get the right diagnosis, which can help determine possible therapy options or participation in a clinical trial for new treatments, educate other family members about their risk for an IRD and connect you with support services to help you live well—despite vision loss.

Why genetic

testing is key

Paid Advertiser

Paid Advertiser

If doctors suspect you have an inherited retinal disease, genetic testing can help uncover the cause and open the door to potential treatments and clinical trials that can save or improve your sight.

Back in bio class, you learned that genes get passed down from your parents to you. You might even remember that they’re made up of DNA, which contains instructions used to produce certain traits, like black hair and blue eyes. But when a change (mutation) occurs on a gene, it can cause the instructions to become scrambled.

In the case of inherited retinal disease (IRDs), for example, three types of inherited mutations are at fault. If you have an IRD, knowing which type of mutation you inherited can help you and your healthcare team determine the best way to manage your IRD—and the only way to know for sure is by having a genetic test.

“There’s not a patient out there who shouldn’t be considered for genetic testing,” says John Kitchens, MD, a vitreoretinal surgeon in Lexington, KY. “Even if the IRD cannot be treated right now.”

“There’s not a

patient out there

who shouldn’t be

considered for

genetic testing,”

John Kitchens, MD

3 main benefits of testing

The American Association of Ophthalmology and the Foundation Fighting Blindness strongly recommend that anyone who is diagnosed with an IRD, or suspected of having one, be considered for genetic testing. Getting tested can help you:

1. Confirm that you have an IRD.

In many cases, IRDs can’t be distinguished from one another based on eye exams and retinal imaging tests alone, since many of these diseases share symptoms and may affect the same cells. That’s where genetic testing steps in. Not only can it help confirm a diagnosis of IRD, but it may also identify the specific gene mutation at fault. This can help people understand how their IRD will affect their vision throughout their life.

2. Find out if you qualify for clinical trials.

New therapies that target specific gene mutations—and that may improve or even save eyesight—are currently being studied. Your test results can help you and your care team figure out if you’re a candidate for a clinical trial.

3. Determine if any of your other family members may be affected.

Because IRDs are hereditary, family members may carry the same gene mutation and not even know it. If one family member has a confirmed IRD, it may help other relatives decide if they should get tested. Children of those with confirmed IRDs may benefit from genetic testing to determine if they also have a genetic mutation, which can aid in early diagnosis and identify possible treatment options.

How testing works

The lab will analyze a sample of your blood or saliva to look for gene mutations that affect vision. Although there are more than 270 genes that can lead to blinding retinal diseases, genetic testing can now identify most of them thanks to advanced technology. It usually takes a few weeks to find out the results.

A genetic counselor can explain the process, and when the results come in, they can help you understand what they mean and how they may impact your treatment options. They can also help you with family planning decisions and connect you with supportive services.

If your insurance company does not cover genetic testing, take heart: The Foundation Fighting Blindness offers genetic testing at no cost to qualified participants. That’s why it’s important to ask your healthcare team about your genetic testing options.

Promising treatments for IRD

Although there are limited therapies currently available, there’s never been more interest in developing treatments for these devastating retinal diseases. Many new technologies and therapies are being researched, with some available to eligible participants in clinical trials. So don’t give up hope of one day finding a treatment for your IRD! Options being studied include:

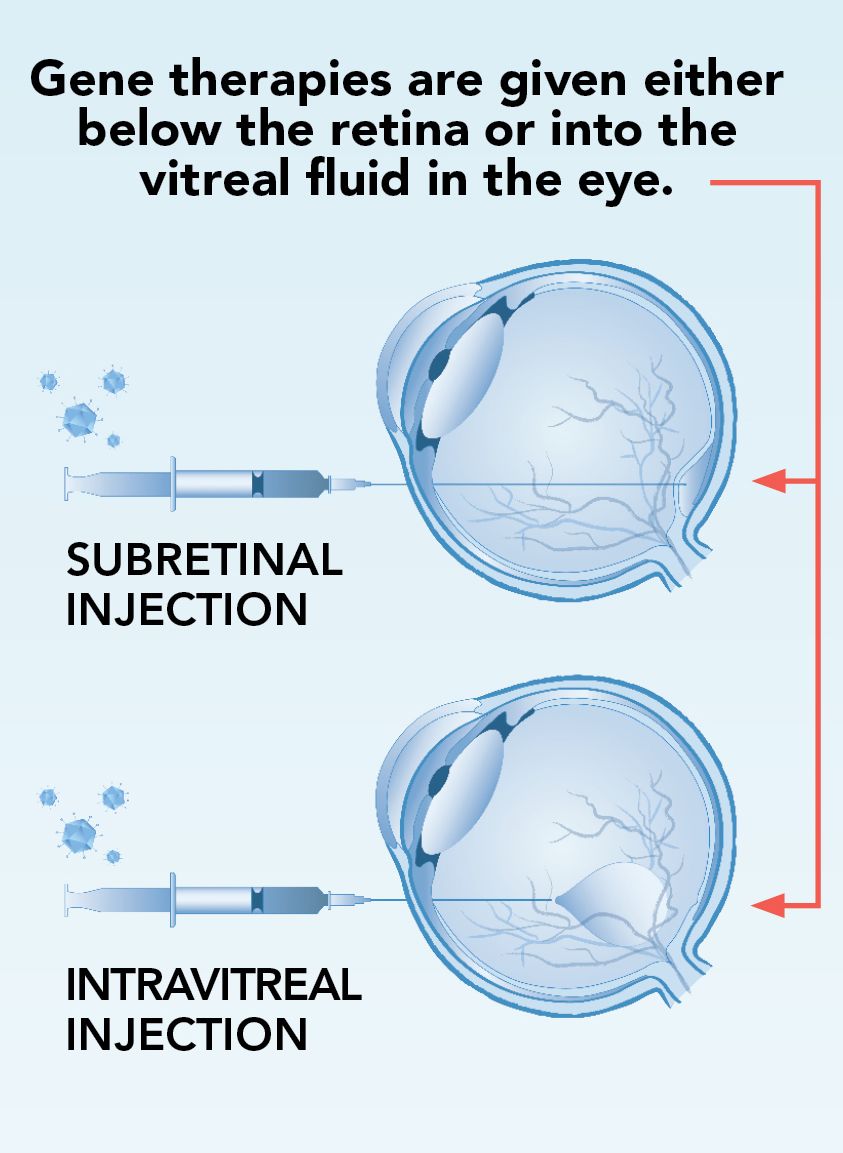

1. Gene therapy:

This treatment is designed to augment (replace) a mutated gene to help stop an IRD from worsening or possibly restore eyesight. Currently, there’s only one approved gene therapy for a specific mutation, but it has dramatically improved eyesight for certain people who have tested positive for that mutation. The good news: There are several clinical trials being conducted on gene therapies to treat different mutations.

2. Neuroprotective agents:

These medicines work to prevent or slow the deterioration of light-sensing cells (rods and cones) in the retina to help safeguard vision.

3. Optogenetic therapy:

This therapy works by using a virus to deliver a gene that expresses a light-sensitive protein to the retina. These proteins may help restore light sensitivity to damaged cones and rods or make other retina cells more responsive to light.

4. Cell regeneration therapy:

This therapy turns stem cells (basic cells that can become any type of cell in the body) into retinal cells that are then delivered into the eye to replace damaged, diseased or destroyed cells that lead to IRD.

5. Retinal prosthetic (bionic retina):

This implantable device uses electrical impulses designed to simulate vision in people with certain types of vision impairment. This device provides limited vision but may help detect higher contrast light sources and objects.

How gene

therapy works

Paid Advertiser

Paid Advertiser

Gene therapy helps treat mutations in multiple ways:

1. Gene augmentation: This therapy helps a mutated gene out by either replacing a missing protein or disabling a protein that the gene can’t produce correctly.

2. Gene editing: This therapy repairs the mutated gene to help it produce the correct proteins.

3. RNA transcript editing: This therapy impacts mRNA, which is the part of the gene responsible for creating proteins.

Is your IRD dominant or recessive?

If genetic testing reveals a gene mutation, you’ll also likely find out if it’s dominant or recessive. Dominant mutations mean that one copy of the mutated gene is enough to cause the disease; recessive mutations require two copies. There are three types:

Autosomal dominant: In this type of inheritance pattern, a person receives one copy of a dominant gene mutation from one parent and one copy of a normal gene from the other parent.

Autosomal recessive: With this pattern, a person receives two mutated genes from each parent. Both parents are carriers of the IRD, having inherited one normal gene and one mutated copy but aren’t affected by the disease. Each of their children has a 50% chance of inheriting one normal gene and one mutated gene and being a carrier, a 25% chance of inheriting both mutated genes and developing an IRD, and a 25% chance of inheriting both normal genes and being neither a carrier nor affected by an IRD.

X-linked disorders: With these, genetic mutations occur on the X chromosome from a mother to child. Because females inherit two X's and males inherit one X, males are more often affected by the IRD, with females often becoming carriers.

Q&A

Paid Advertiser

Paid Advertiser

Accessing a clinical trial

Q: My retinal specialist says I might benefit from a clinical trial when one becomes available for my type of retinal disease. How can I get involved?

A: You can learn about clinical trials done nationally at ClinicalTrials.gov. If there is a trial that is not local, your retina specialist may make a referral if you meet the trial criteria.

Is genetic testing ok?

Q: My son’s doctor suspects he has an inherited retinal disease and recommended genetic testing. What are the pros and cons?

A: It’s important that your son see a retina specialist with an interest in inherited eye diseases. Typically, testing is done with ophthalmic imaging—e.g., retinal photos, OCT test, visual field testing and electroretinography, among others. Genetic testing can be ordered directly through a company that does these panels, or you may be referred to a physician who is a geneticist. The benefit of genetic testing is that it enables us to know which gene is affected, so if there is a clinical trial or treatment involving your specific genotype, you can know

and be involved.

Help me adjust to IRD!

Q: I was recently diagnosed and am having a difficult time coping. What can I do to stay as independent as possible?

A: You may want to consult with a low vision specialist, an optometrist who specializes in helping you learn how to make the best possible use of your current vision. Also, there are many support groups, whether local and in-person, or online.

Our expert: Sophie Bakri, MD,

Professor & Chair of Ophthalmology, Vitreoretinal Diseases and Surgery, Mayo Clinic, Rochester, MN

“Vision loss can’t

slow us down!”

Paid Advertiser

Paid Advertiser

Paul Castle, Adriann Keve and Sean Brennan have lived with inherited retinal diseases for more than 20 years, so they know a thing or two about managing day-to-day life with vision impairment. Read on for their top tips—and ask your healthcare team if they could help you, too!

“I have more hope than ever!”

____________________

Paul Castle, 32

Seattle, WA

Diagnosis:

Retinitis Pigmentosa

As a child, Paul Castle was considered “accident prone” and has the scars to prove it. Since he had glasses starting at age 5, it didn’t occur to the family that it was a vision issue. But over the years, Paul’s sight worsened.

After struggling to see during his driver’s test at age 16, Paul made an appointment with an ophthalmologist, where he was officially diagnosed with retinitis pigmentosa, an inherited retinal disease (IRD) that damages the light-sensitive cells in the retina, causing a slow loss of vision over time.

Today, the 32-year-old visual artist, children’s book author and husband is embracing many roles as he navigates the world with progressive vision loss.

“I’ve lived half my life with the knowledge that this condition would slowly rob me of my vision,” he says. “Yes, I have a disability, but it doesn’t mean I’m unable to do incredible things!” Here, Paul shares the tips that help him thrive day-to-day:

Paid Advertiser

Consider genetic testing.

In 2017, after hearing about more and more progress being made with gene therapy, Paul decided it was time to get tested. He discovered he had X-linked retinitis pigmentosa (XLRP), which predominantly impacts men. Thanks to getting tested, Paul started researching clinical trials and was in luck; his particular genetic results qualified him for a gene therapy clinical trial, which he started in mid-October 2022. “It’s given me hope that I can retain my sight, and maybe in the future even gain some back!”

Spread awareness.

Paul discusses life with an IRD on various platforms—including Instagram @PaulCastleStudio and his website paulcastlestudio.com. “I want others to know that a disadvantage doesn’t diminish you; it’s your opportunity to shine,” he says.

Use technology aids.

“While my vision has diminished over time, tech has continued to improve,” says Paul, who adds that tech has been invaluable while he works on his children’s book The Pengrooms (available wherever books are sold). For artwork, he uses an illuminated tablet and he uses his phone’s camera feature to take photos and zoom in on rooms and scenes that might otherwise be difficult to see. Paul has also started learning Braille and uses an artificial intelligence digital reader to read text from print surfaces or electronic screens that don’t offer audio.

Embrace mobility aids.

Eight years ago, Paul started using a white cane. “Having something that helps people know I have low vision actually makes me safer.” Last year, Paul also got a guide dog, Mr. Maple, who has boosted his confidence exploring the city. “My invisible disability is now very visible, and people are very responsive to a cane and guide dog.”

Photo by Morgan Belieu

Photo by Morgan Belieu

Find the silver lining.

“I’ve met the most wonderful, supportive community of sighted and low-vision people,” says Paul. “My disadvantages have also opened new doors and ultimately have allowed me to experience life with greater appreciation.”

Photo by Marina's Photography

Photo by Marina's Photography

“Focus on what you can do!”

____________________

Adriann Keve, 40

Jacksonville, FL

Diagnosis:

Stargardt Disease

Adriann Keve first started noticing vision troubles when she was eight and unable to read the board in class. “By age 10, I was struggling even with glasses and sitting in the front row,” she recalls.

Adriann eventually saw a specialist at the University of Iowa Hospital, and was diagnosed with Stargardt disease.

While today her vision is around 20/400, she focuses on the positives the condition has brought into her life. “I’ve gotten to meet so many amazing people and had so many opportunities and experiences that I probably wouldn’t have had, had it not been for having an IRD.” Here are her tips for others living with vision loss:

Key into other senses.

“When I’m cooking, I’ll smell a spice container to see what it is rather than trying to read the label, or I will identify a cleaning product by the shape or size of the bottle rather than by reading the label. In fact, I rely heavily on my sense of touch when it comes to identifying most smaller objects.”

Find activities you enjoy.

“My husband and I also go for walks and hikes, and I will use a white cane when necessary. I’ve even been able to try out some sports through a local adaptive sports program called Brooks Adaptive Sports and Recreation. I’ve tried golf, bocci, cycling, archery, water skiing, surfing, and more!”

Photo by Marina's Photography

Photo by Marina's Photography

Do your own research.

“It’s extremely important for someone with an IRD to educate themselves about their condition, because some healthcare professionals may not be aware or well-informed. The Foundation Fighting Blindness, for which I am a chapter president in Florida, is a great resource for anyone with an IRD. It has lists of specialists who are knowledgeable in the different conditions and can connect newly diagnosed patients with other people living with IRDs, who have a wealth of knowledge they can share from personal experience. It’s also important to continue to see a specialist after your diagnosis, even if you were told there’s no cure. They can monitor you, and inform you about clinical trials.”

Stay positive.

“I often hear people who are newly diagnosed talk about all the things they won’t be able to do, but I’d like to encourage any newly diagnosed person to consider how they can do things. It may look different from what you originally had in mind, but you can almost always find a way to pursue that career, or cultivate that hobby, or achieve that goal.”

Photos by 4eyesphotography

Photos by 4eyesphotography

“Never give up!”

____________________

Sean Brennan, 37

New York, NY

Diagnosis:

Choroideremia

When Sean Brennan was a kid, the family story was that he was just “night blind.” He struggled to play games with other kids in the neighborhood when the sun was setting because he “kept running into things.” But when he hit 16, it was no longer fun and games: He would be driving soon, his mother realized, and she was worried. So, she took him to a vision center. The doctor said, “It looks like choroideremia,” which was later confirmed by genetic testing.

Today, 21 years later, Sean is a musician living in New York (you can hear his band, Strange Weather, at whatstrangeweather.com, or on most nights in Brooklyn and surrounding areas) and is eagerly awaiting the day he can join a clinical trial for his IRD.

Photo by 4eyesphotography

Photo by 4eyesphotography

Be open with people.

At first, Sean didn’t want the negative attention, but now he tells people as soon as he meets them. That has two benefits, he says: They understand him better, and it brings them to a realization of their own vulnerability and mortality. “None of us is immune,” he says. “We all have to deal with issues in this life, and it unites us when we realize that we’re all in this together.”

Accept help from loved ones.

Sean thrives on being an independent person, but he’s learned to lean on his wife, Callie. “She’s ferociously protective of me,” he says. For example, she holds his thumb in dark places. “She taps once to signal me step up, twice to step down. I really can’t imagine what my life would be like without her.”

Seek understanding from others.

This past June, Sean and Callie went to a conference for people with choroideremia, where his band performed at the grand finale dinner. “We all understood each other. One person would meet another, and we would poke each other in the belly because we couldn’t see each other’s outstretched hands. It just all made sense.”

Consider gene therapy.

“Years ago, I didn’t quite get what gene therapy could do for me,” Sean says. “But now I know that it’s the light at the end of the tunnel. Even those who might be too old to benefit from it themselves are excited because it will benefit their children and their grandchildren and all the generations to come!”

Diagnosed with choroideremia?

Sean recommends reaching out to The Choroideremia Research Foundation (CRF). The CRF was founded in 2000 and provides international patient and family education, support, advocacy, and funds research toward a treatment or cure for choroideremia (CHM). Since its inception, CRF has funded approximately $5M in research including support of clinical trial development, cell and animal models, and better understanding CHM pathophysiology. Services include virtual events such as webinars, special interest group meet-ups, socials and 1:1 support. In-person events include conferences, town hall meetings and scientific symposia. For more information, follow CureCHM on social channels or visit curechm.org.

Special thanks to our medical reviewer:

Sophie Bakri, MD

Professor & Chair of Ophthalmology, Vitreoretinal Diseases and Surgery, Mayo Clinic, Rochester, MN

And thanks to the Foundation Fighting Blindness for their review of this publication.

Maria Lissandrello, Senior Vice President, Editor-In-Chief; Lindsay Bosslett, Associate Vice President, Managing Editor; Joana Mangune, Senior Editor; Marissa Purdy, Associate Editor; Erica Kerber, Vice President, Creative Director; Jennifer Webber, Associate Vice President, Associate Creative Director; Suzanne Augustyn, Art Director; Ashley Pinck, Associate Art Director; Molly Cristofoletti, Graphic Designer; Kimberly H. Vivas, Vice President, Production and Project Management; Jennie Macko, Senior Production and Project Manager; Rachel Pres, Director Digital Production, Project Management

Dawn Vezirian, Vice President, Financial Planning and Analysis; Donna Arduini, Financial Controller; Tricia Tuozzo, Sales Account Manager; Augie Caruso, Executive Vice President, Sales & Key Accounts; Keith Sedlak, Executive Vice President, Chief Growth Officer; Howard Halligan, President, Chief Operating Officer; David M. Paragamian, Chief Executive Officer

Health Monitor Network is the nation’s leading multimedia patient-education company, with websites and publications such as Health Monitor®.

For more information: Health Monitor Network, 11 Philips Parkway, Montvale, NJ 07645; 201-391-1911; healthmonitornetwork.com ©2022 Data Centrum Communications, Inc. Questions? Contact us at customerservice@healthmonitor.com

This publication is not intended to provide advice on personal matters, or to substitute for consultation with a physician.

NAJ23-DG-IRD-1NAJ

Health Monitor Medical Advisory Board

Michael J. Blaha, MD, Director of Clinical Research, Ciccarone Center for the Prevention of Cardiovascular Disease; Professor of Medicine; Johns Hopkins

Leslie S. Eldeiry, MD, FACE, Clinical Assistant Professor, Part-time, Department of Medicine, Harvard Medical School; Department of Endocrinology, Harvard Vanguard Medical Associates/Atrius Health, Boston, MA; Chair, Diversity, Equity and Inclusion Committee, and Board Member, American Association of Clinical Endocrinology

Angela Golden, DNP, FAANP, Family Nurse Practitoner, former president of the American Association of Nurse Practitioners (AANP)

Mark W. Green, MD, FAAN, Emeritus Director of the Center for Headache and Pain Medicine and Professor of Neurology, Anesthesiology, and Rehabilitation at the Icahn School of Medicine at Mount Sinai

Mark G. Lebwohl, MD, Dean for Clinical Therapeutics, professor and chairman emeritus at Kimberly and Eric J. Waldman Department of Dermatology, Icahn School of Medicine at Mount Sinai, New York

Mary Jane Minkin, MD, FACOG, Clinical professor in the Department of Obstetrics, Gynecology, and Reproductive Sciences at the Yale University School of Medicine

Rachel Pessah-Pollack, MD, FACE, Clinical Associate Professor, Division of Endocrinology, Diabetes & Metabolism, NYU School of Medicine, NYU Langone Health

Julius M. Wilder, MD, PhD, Assistant Professor of Medicine; Chair, Duke Dept of Medicine Diversity, Equity, Inclusion, and Anti-racism Committee; Vice Chair, Duke Dept of Medicine Minority Retention and Recruitment Committee; Co-Director for the Duke CTSI- Community Engaged Research Initiative